Finding Palestine: a short tour of the shrinking West Bank

2017 marks the 100th anniversary of the Balfour Declaration and the 50th anniversary of Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and Gaza strip. Spending a few months as a trailing spouse in neighbouring Jordan, I make time to visit, with around 70 words of Arabic and no guide book.

The cab driver who takes me from Amman to the border says he paid 50,000 dinars (USD 70,000) for his second-hand car and the licence to operate this route. “Jordan government is thief,” he says. “Thief.” Like nearly half of Jordan’s population he is of Palestinian origin. His family left the small city of Nablus after the 1967 Six Day War, when the Israeli army routed the combined forces of Egypt, Syria and Jordan and occupied the Palestinian territories. Nablus is only 100 kilometres from Amman, but he has never been there.

The King Hussein Bridge that crosses the River Jordan to the West Bank is as tiresome to traverse as tripadvisors and travel bloggers warn. The cavernous Jordanian departure hall is spattered with spilt coffee and has the most disgusting public toilet I have seen anywhere west of China. There’s a ten dinar ‘exit fee’ and a seven dinar bus fare for jolting through a short buffer zone and over the bridge to the side that Israel occupies. There, the driver and local passengers assume a submissive patience as an Israeli border guard peremptorily waves the bus to a parking spot. We sit in sweltering heat for twenty minutes, engine idling, doors closed, until allowed into a fiercely air-conditioned arrivals area, as small and clean as the Jordanian side was large and shabby. After a protracted baggage check we queue up with passports. The woman who inspects mine asks where I am going and why and then says take a seat, you will be called. There is no seat to take; the dozen or so provided are already overflowing with families that I take to be Palestinian. So I sit on the floor and get out my book, which turns out to be tedious. Quite soon an official comes out of a side room and asks for my father’s full name. This seems promising: just a form that needs filling in, perhaps? Yet, while most of the other travellers eventually trickle through, I am left sitting for another two and a half hours regretting my skipped breakfast, for there is not so much as a coffee machine here. What the fuck are they doing? Googling me? Developing a dossier? Then, talking to an elderly man who has been dozing next to me, I discover that there is free wifi here, so I turn on my phone to e-moan to my family. Minutes afterwards my passport is returned and I am permitted to proceed, wondering if maybe they were just waiting for me to switch on so they could read my WhatsApp or whatever. Not that I know anything about surveillance. Except that it invariably arises from and ends up reproducing mistrust and enmity.

Ramallah—reached by a short bus ride to Jericho and then a shared taxi up the escarpment—is a pleasant surprise. Its small centre is bustling and seems relaxed. Quite narrow streets, on a human scale (not yet sliced through by freeways), are lined with local stores (not global brands), restaurants and coffee shops. Some cafés are crowded with men only, sucking pipes and playing backgammon. Others are smarter and trendier: espresso machines, mixed groups, tables of women friends, some with hair uncovered, enjoying frappucinos. I hear there are also places to drink alcohol and dance the night away, but don’t bother looking for them.

Spreading from the centre are several new and quietly affluent commercial and residential districts. For Ramallah is the seat of the Palestinian Authority—the ‘autonomous’ civil administration of the West Bank and Gaza, set up after the 1993 Oslo Accords between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organisation. Its authority doesn’t reach far, but it nets USD 2.5 billion a year in revenuesfrom a Palestinian GDP of USD 13 billion, along with hundreds of millions of aid dollars. That’s enough to make life fairly comfy for a political and administrative elite and, unless the widespread reports of the Authority’s chronic corruption are all false, some of that elite are more comfy than they should be. On a northern hilltop just out of town stands a new presidential palace, a deluxe ostentation for a territory half the size of Yorkshire. (I am told later, and am glad to hear, that it has been turned, after public outcry, into a public library.)

Back downtown, cheap clothes and electrical goods from Turkey are the staple of most shops. A fruit market overflows with fresh produce, more sumptuous by far than any I’ve seen in Jordan. It comes out of boxes printed in Hebrew script, so I infer that it originates from Israeli farms. I can’t help imagining that Arabs well beyond Palestine must envy and resent Israel’s extraordinary success in advanced, irrigated agriculture, greening the desert, almost as much as they must hate its military strength and proficiency with violence.

Happily, no one seems to resent me. I try one morning to buy a single, one-shekel (USD 25 cents) bread and sesame roll from a baker’s stall on the market, but neither I nor the trader have change so he just gives me the roll and waves me away. I return later with a shekel coin but he refuses it. That evening, as the traders are covering their stalls for the night, I try to buy a bunch of grapes, smaller than the ten-shekel mounds that seem to be the normal unit of sale. This stallholder too gifts me the bunch, and insists on adding a free plastic bag. I would like to refuse the latter, because I hate the plastic trash that clogs every gutter and alleyway of every town, blows across every desert and scags on every thorn bush and olive tree that I have so far seen in this part of the world. But the proffered wrapping is clearly integral to the trader’s idea of good service, and it would hardly do to repay his kindness with green evangelising, even if my smattering of Arabic were up to the task.

I stay in Area D Hostelnext to the market. (The name is an ironic reference to the ‘A’ to ‘C’ zoning of the occupied territories, as established in the Oslo Accords.) It’s the kind of place where backpackers 40 years younger than me share dorms and bathrooms and look a bit askance at the old guy padding down the corridor with his toothbrush. I chose it because they also offer ‘political tours’—a possible short-cut to things that interest me; and I am curious, too, to get the measure of international solidarity tourism. There’s little doubt this was the Swiss founder’s target market: the common sitting area is stocked not just with dog-eared, outdated Lonely Planet guides, but with (equally outdated but much less dog-eared) reports from think tanks and NGOs. The walls are hung with UN agency maps showing security barriers, checkpoints, closed areas and the 150 Israeli settlements, housing more than half a million people, now established within the West Bank (which is home to around three million Palestinians).

Mohammed, who is maybe 30, speaks English fluently and has worked in Area D for four years, is in charge the day I arrive. That evening, I sit with him and a colleague of his, Jihad, who is new to the job, in a large room set aside for smoking, drying the hostel laundry and for the duty staff to sleep in. The hostel’s not busy, and Mohammed seems content to spend a couple of hours telling me about Palestine’s woes. Perhaps this is also by way of training for Jihad.

The list of grievances is long. Families are evicted from places they have lived for generations, and their homes are demolished, for spurious reasons—they cannot prove land title, or show planning permission, or are deemed to be living on an archaeological site—and then Israeli settlers move in. Israel controls the mountain aquifers, taking nearly all the water for its own farms and people. Israel has strangled the Palestinian economy, there are no jobs and it is ever harder to get work and travel permits in Israel. People must queue for hours to cross into East Jerusalem. Most are denied entry, and so many are divided from their families. It is altogether impossible to get in to Gaza.

Mohammed presents this as a story of progressive, calculated dispossession, in which Palestinians suffer to atone for the sins of Europe:

There were always Jewish communities in Palestine, and they were welcomed and well treated. But after the Nazi holocaust—and we don’t deny that happened, or how terrible it was; we are not anti-Jewish, I have Jewish friends and even speak some of their language and you speak even more, isn't that right, Jihad? But after the holocaust, the rest of the world was afraid to say no to the Zionists and always supported them. You’ve seen their flag: the blue star between two blue lines? One of those lines is the Mediterranean and the other is not even the River Jordan, it is another river, beyond—what's it called, Jihad? Their idea is that all of this should be Israel and steadily, steadily, they are pushing us out. You’ve seen the maps . . .

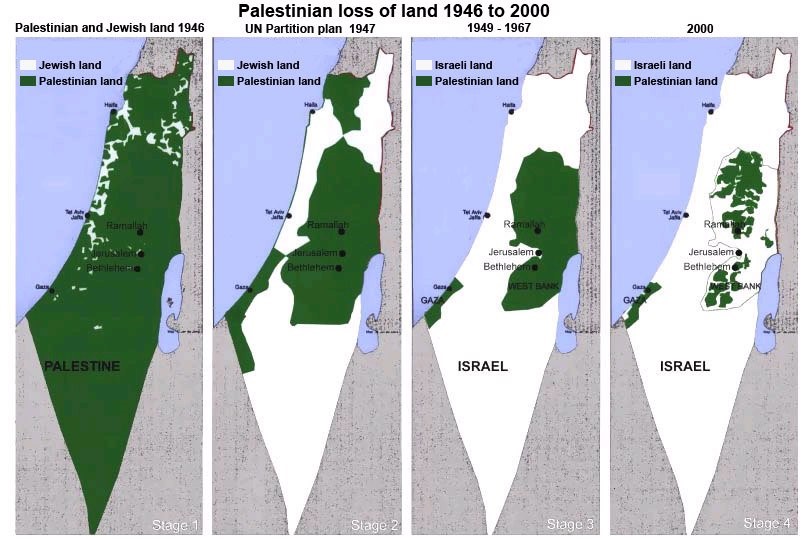

It’s not just the UN maps he means, but a graphic developed years ago, free photocopies of which lie on a table for the edification of guests:

Dramatic though they are, these images strike me as misleading because of what they leave out—and even conceal in the rubric of ‘stages.’ This is not to deny aggressive, Zionist expansion: Israeli scholars have themselves produced compelling evidence of early Israeli leaders’ determination to ‘cleanse’ land of Palestinians. But Zionism has been helped along by a shifting cast of players pursuing their own interests, cynically and usually incompetently.

Britain originally endorsed the idea of “a national home for the Jewish people” (in the 1917 Balfour Declaration) to bolster and legitimate British ambitions in the wider region: snatching the baton, and the oil, from the collapsing Ottoman empire. Having secured that prize, in the form of a ruling ‘Mandate’ granted by the League of Nations, Britain in fact strove to limit Jewish immigration, after violent protest and revolt by the Arab population—for it is certainly not the case that Palestinians “always welcomed” Jewish communities. Britain even turned away shiploads of Jewish refugees from Europe in 1947. France meanwhile actively encouraged Zionist militia: largely, it has been argued, in revenge for British meddling in French imperial possessions. (James Barr, A Line in the Sand, Simon Schuster, 2011).

As Britain’s mandate neared its 1948 deadline, the UN came up with a partition plan that—with the scale of the Nazi holocaust revealed, and huge numbers of Jewish refugees in Europe—set aside just over half of Palestine for Israel (although a great deal of that portion, the southern cone, comprised the inhospitable Negev desert). It’s not too surprising that that the Palestinian leadership and Arab League should have rejected this. But when Egypt, Syria, Iraq and Jordan (at that time, ‘Transjordan’) took on the new, unilaterally declared state of Israel in the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, they not only failed to destroy it but ended up ceding to it much more Palestinian territory than the UN had originally proposed. (Hence the difference between the graphic’s ‘Stage 2’ and ‘Stage 3’.) And the worst of it was that the Arab allies in that war were aiming not to establish a sovereign Palestinian state but, rather, to carve up and annex Palestine for themselves. (Jordan hung on to the West Bank until losing it to Israel in 1967.) So, whilst Palestinians have every cause for bitterness, they’ve got everyone to blame for their predicament, not just Israelis.

I don’t make this case to Mohammed and Jihad but I do ask what they think of Mahmoud Abbas, the Palestinian president. They look downcast. There are problems of corruption and leadership, they say. (And, it seems, growing intolerance of Palestinian dissent.) But Yasser Arafat, the PLO and Fatah leader of old, he was better, a great man.

I’m not so sure. In 1994, Edward Said denounced the Oslo Accords as “an instrument of Palestinian surrender” that allowed the Palestinian Authority no larger role than “providing services to residents.” Arafat, Said argued, had missed earlier chances for a better deal, and was now signing documents he had not even read because he was flattered that Israel recognised him as the representative of Palestinians, and needed to see off political rivals—including the emergent Hamas. Said raged:

What sort of leaders accept such an arrangement on behalf of their people from a state and a mentality that has waged unremitting war against that people for at least half a century? What sort of leaders describe their failures as a triumph of politics and diplomacy even as they and their people are forced to endure continued enslavement and humiliation? Who is worse, the bloody-minded Israeli ‘peacemaker’ or the complicit Palestinian? When will the two peoples wake up to what their leaders have wrought?

On a global stage, Said—author of Orientalism, which shaped the post-colonial discourse of liberal academics worldwide—was the best known and respected Palestinian intellectual of the 20th century. After this outburst, the new Palestinian Authority banned his books.

I don’t share these thoughts either. Mohammed promises that, although no tour was planned this week, he’ll fix a trip to Hebron for me the day after tomorrow—he makes a few calls—and there I will see for myself.

With that sorted, I spend the next morning wandering round town and the afternoon looking for some countryside. Specifically, I head to Deir Ghassaneh, a village recommended in the guidebooks I’ve now had a chance to thumb. It’s about a half hour ride in one of the ‘service taxis’ that ply the West Bank. These are orange coloured, eight seater minibuses, in good condition and comfortable, with a whole seat to yourself—not like the crammed and battered taxi vans of East Africa, although driven with at least as much reckless speed.

I’ve seen pictures of wild flowers and grasses springing from the desert after rain, and have read accounts of pleasant walks through rural Palestine, but in the long, dry season of our sojourn I’ve found little in these parts that matches my idea of beauty. From Jordan, escarpment views are impressive: hills in various shades of grey and ochre, sweeping to the far horizon, but to me this looks like the Yorkshire dales after 200 years of global warming, and it makes the heart shrivel. Closer up, you see the hills are dotted with clumps of bush and what looks like dead, blackened heather. It’s hard to believe this is enough to support the occasional browsing goats. Odd to think this could ever be seen as a land flowing with milk and honey, when it must be so hard to squeeze either from it.

On the West Bank, I am naively shocked by the population density. Billions of tons of desert rock have been quarried, crushed and refashioned into villages and towns garlanding almost every hill. (The newest and shiniest, I am beginning to understand, are the Israeli settlements, and there is nothing tentative or provisional about them; most are highly developed, urban areas.) Rural Palestine is hard to find.

Yet, in the last ten minutes of the journey, semi-urban sprawl gives way to dusty olive trees in rocky terraces, and Deir Ghassaneh turns out to be pretty. Quiet; peaceful; quite prosperous; possible to forget the towers of Tel Aviv in the hazy distance. Which is why it’s in the guidebooks—because it is atypical. Who, after all, wants to see the ordinary and unpretty?

I potter round the restored, mediaeval village centre. A couple of tethered donkeys doze under an olive tree. Two little girls playing in the street stand and stare, ask my name and run away giggling when I answer. I say hello to an old guy passing by who then stops to shake hands and exchange greetings properly. Four younger men sitting outside a half-built house shout and wave at me to join them, so I sit for a while and am plied with dates and coffee. One of my hosts makes me a gift of a plastic-packaged stick from a tree in Saudi Arabia—a natural toothbrush, it seems—and a string of plastic prayer beads. All this in a mix of gestures, broken English and plenty of shukrans from me. I ask if they are brothers. They say they are cousins and all unemployed (“What work do you do?” is one of my star sentences in Arabic), and I say I am unemployed too. Another guy in a BMW sports car drops by briefly but I don’t learn his employment status. The man who gave me the toothstick and the beads has a crutch and shows me a long scar on his left shin. I say “Accident? Car accident?” and he says yes, but then later “Not car. Israelis.”

The ride back to Ramallah is very jolly. I am the first passenger to board but we stop and hoot outside a village house and a woman, fortyish, gets in with four daughters. She has six daughters altogether. This is conveyed by the eldest, who speaks a fair bit of English and is assigned by mum to question me. “You have grandchildrens?” They all laugh a lot at whatever I say. The interpreting daughter has just finished a law degree at Birzeit university, which we drive past. She tells me it is “very big and very beautiful.” (To me it looks concrete and depressing.) She is hoping to do a Masters in “Law of Childrens” in France, because “French is easier language to learn.” Good for her.

We are stopped at an army checkpoint. (There are many along the way, concrete structures with barriers at the ready, but most are unmanned, just there to make the place easy to lock down when deemed necessary, I suppose.) As we move off the driver takes his hands from the wheel to make a sign of being throttled, and says "Israel!"

Back at the hostel, there is no sign of Mohammed or Jihad and no-one knows anything about my Hebron tour. The young man on duty tonight, curly haired and less chatty, spends all evening in the smoking room playing backgammon with a friend, but he makes a phone call and says no problem, someone will meet me in Hebron tomorrow. In the morning, there is no sign of curly- hair, and the young woman now in charge knows nothing about my trip. If this is the mettle of the anti-Zionist struggle, it’s in trouble. Oh well, I’ll just go alone. But first I’ll pass by Bethlehem.

No olive groves to relieve this trip. The orange van weaves and dips, up, down, round east Jerusalem, a puzzle of roads, some closed to our registration plate, a valley with quarries and goats living on quarry dust, settlement-crowded hilltops, some precipitous. I don’t really know what I’m seeing, but can see enough to know it’s complicated.

Bethlehem’s a scrappy, undistinguished town with a done-up ‘old’ quarter that is, in fact, many centuries younger than its most famous story. This anachronistic frame does nothing to deter daily busloads of tourists from all over the world. I stand aside while one coach disgorges a couple of dozen large and brightly dressed ladies from Guinea Bissau. They trek up to Manger Square and the Church of the Nativity, which stands on the ruins of the ruins of the first church built there several hundred years after the miraculous birth. And they line up for hours to pass through a crypt built over the alleged birthplace. (Which, I can’t help supposing, was probably designated by some third or fourth century pilgrimage committee.)

A tour guide offers to help me jump the queue for a small consideration, but I am more interested in watching the tourists. They mostly look hot and tired. As I emerge from the cloisters’ merciful shade, a mosque on the other side of Manger Square is calling for prayer. Several dozen men have laid down mats, between cars parked all over the square, to answer the call. A Russian tour group stops to capture the moment on their phones.

A short way uphill, past an old market restored by a grant from USAID, is a Lutheran Christmas Church “inaugurated by Kaiser Wilhelm II during his visit to the Holy Land in 1898,” the sign says. That would have been just before the genocide in Namibia, the one almost no one remembers. Not far off is a venerable Terra Sancta College (Franciscan), which started several centuries earlier. On Shepherds Field (where shepherds washed their socks by night, as my Church of England primary school playground had it) stands a Greek Orthodox church. Dotted around town are monasteries, guest houses etc run by numerous other sects, witness to the endless divisibility of faith. If people can find points on which to disagree they invariably will.

The tour groups don’t start massing until mid-morning and before then the old town is quiet and pleasant. Prospecting for an early breakfast the next day, I am captured by the proprietor of a little kitchen as he sallies out with a tray of sweet tea for neighbours who are still setting out their stalls. “You are looking for me!” he declares. Irresistible charm.

He settles me in a plastic chair on the shady side of the street and, after establishing my nationality, says:

“You know Susan Scott? Is from Scotland. Is singer. Is coming here to sing. Is going to sing with Alan Gates, but he isn’t come, so she sing herself. Has good voice!”

Moments later he returns with a photograph of himself, round, middle aged, grizzle chinned, sitting beside a pale, clean-cut youth with a shisha pipe.

“You know who this?” The youth looks vaguely familiar. David Cameron while still at ’varsity, perhaps?

“Is Conor O’Brien!”

Ah. Irish. Grandson of Conor Cruise O´Brien?

“Not Irish.” (Slightly deprecating, disappointed.) “Is American. Is coming here making film with me.” I feel bad about letting him down.

A regular customer shuffles up, an elderly man with a crutch, and I learn from their greetings that the jovial proprietor is called Samir. He goes in to brew up more cardamom coffee. Singing.

Bethlehem’s other tourist attraction is the wall. In the early 2000s, during the second intifada against the occupation, Israel started erecting a ‘security barrier’ that now stretches for hundreds of miles, hemming in and at many points encroaching upon the West Bank. For much of its length, the barrier consists of fences, razor wire, etc. Around Bethlehem it is a reinforced concrete wall, eight metres high, with cameras and watchtowers, dividing neighbourhoods. This abomination has become a focal point for displays of solidarity with Palestinians: Pink Floyd have played concerts here; Pope Francis prayed by the wall; the British street artist, Banksy, has painted murals on it, and recently established the Walled-Off Hotel at a point where the wall skirts the main road to Jerusalem.

Before visiting Banksy’s witticism, I loiter a while round the Aida Refugee Camp, which huddles under the wall. The word “camp” is misleading. This is, rather, a slum inhabited by several thousand people whose families fled here 68 years ago, during the 1948 war and have not yet found the means to move on. There are 19 such camps in the West Bank, with a combined population of 809,000, and eight larger ones in Gaza, accommodating another 1.3 million people. (UN numbers.) In Africa and Asia I’ve seen more squalid slums than Aida, but none that is quite so desolate, squeezed as it is between the Israeli wall, whose lower reaches here are piled with mounds of rotting rubbish, and the more urbane walls of Bethlehem’s new Intercontinental Hotel. It makes you feel ashamed to be human.

Between Aida and the Walled-Off Hotel there’s about a kilometre of wall enclosing Rachel’s Tomb, a site of religious significance for Judaism, Christianity and Islam, but from which Christians and Muslims are now excluded. Pasted on this stretch, alongside murals and graffiti, is a series of posters bearing snatches of testimony from the refugees and other local Palestinians, including children. Some of this is moving, but I can’t help feeling it is mainly, perhaps only, moving to those who have come ready to be moved.

Less touching is the graffiti concentrated in the more visible stretches, close to Banksy’s hotel, contributed by visiting groups and individuals. (Spray cans and other art resistance materials available at the shop inside.) Granted its sincerity—outrage is a natural enough reaction here—one wonders more about its value. Spray your say and go home feeling on the side of justice. Does this do anything to touch the brute simplicities of power? Well, maybe a tiny bit. I don’t blame Banksy, even admire him. I find the irony that marks his work more congenial than righteous anger, and perhaps it draws more attention.

If the wall at Bethlehem invites easy outrage, Hebron is more weird and disturbing.

It’s a bigger town, a city. Busy, unglamorous, repetitive; jammed traffic honking, broken pavements, cheap stores and kebab shops; a biggish population with modest means and, I guess, mostly modest wants: a hair-cut, a new pair of shoes, fried chicken and a Pepsi. Much like everywhere that’s not in a guide book.

But Hebron is also the alleged birth and burial place of Abraham—revered, in different ways, by Judaism, Christianity and Islam—and the site of periodic religious violence for more than a thousand years. From 1968, after Israel seized control of the city in the Six Day War, a handful of Jewish settlers set out to reclaim this place for their faith, re-establishing a Jewish community that imperial Britain evicted, in an effort to keep the colonial peace, in the 1920s. A 1997 (post-Oslo Accords) agreement with the PLO brought a fifth of the city under formal, Israeli jurisdiction, but the Jewish settlers still number only in hundreds.

I don’t know how or who to ask the way to this quarter, but am guided by the star of David, the Israeli flag unfurling the breeze on a hill above the old market and visible to the whole city. I show my passport at a checkpoint protected by slabs of concrete blocking off the road and the market’s bustle, and I pass through a steel turnstile into a deserted street of rusting, shut-down shopfronts. Pasted on them are notices stating in Hebrew, Arabic and English that these “Arab” stores were closed because of terrorist attacks.

It is Saturday, the Sabbath, and at first I find no signs of life. Walking up towards the flagpole I pass a group of dawdling teenage boys with skull caps and side-curls. Further up, by another military checkpoint, is a row of new but quite simple duplex houses, from which a young couple is setting out with a baby in a pushchair. We exchange nods.

Turning back, I meet, coming up the hill, a group of around fifty people, families walking together: men in black Orthodox dress with tassels at the waist, women in neat, long skirts, small children with straw coloured hair, several young men carrying automatic weapons—M16s I think, though I don’t know much about guns—not casually borne, slung over their shoulders, but held upright, close against their chests, like some religious artefact. It’s a curiously complex sight, the blend of apple pie family sweetness and swaggering, defiant assertion.

They are returning from the holy place, which I find a couple of hundred yards down the deserted street, past a community centre and café that is closed today, past a group of Orthodox youths kicking a football on an empty lot that is astonishingly free of litter, past a concrete bench in a villagey space with well-kempt and watered grass—real grass!—past a plaque commemorating a Jewish couple shot dead by Palestinian gunmen some years back. The plaque notes that the couple were childless, evidently finding this a poignant fact, an erasure, a dead end. I do not find a plaque to commemorate the 1994 mass murder, by a Jewish 'shooter', of 29 Muslims praying in the Ibrahimi Mosque. This is the holy place: converted a thousand years ago from a Jewish temple built a thousand years earlier above the Cave of the Patriarchs where Abraham, Sarah, Isaac, were reportedly laid to rest.

The entrance checkpoint is guarded with scanners, steel turnstiles, guns. I don’t go in. Against the wall, at an unguarded spot, is a stone staircase with a small plaque stating that this holy place was taken over by Muslims in 1267, and until 1967 Jews were allowed no further than the seventh step. Today, the plaque adds, the especially devout choose still to pray upon the seventh step. And, sure enough, a black coated figure is kneeling there, rocking in a way that, as I approached, made me think he might be autistic.

Back by the entrance checkpoint, in the shade of a couple of trees, two separate groups are seated on the ground, receiving Sabbath teachings. One group all men; the other women, mostly young, well dressed and pretty, and their pretty children. Both groups are addressed by men, standing. Away from them stretches a large, pristine lawn, backed by the crumbling, biscuit coloured ruins of ancient dwellings. It’s quite the pleasantest spot I’ve found in Palestine.

A pretty scene, yet repellent. I feel it’s wrong to do this to children. These pretty families could be living safely in Tel Aviv, almost as safely in Jerusalem, more safely in London, Paris, New York. Why choose to raise children here, surrounded by many tens of thousands of people who feel—reasonably enough—that you’re systematically dispossessing them? People who mostly hate you and at least some of whom would seize the chance to kill you? To choose this for your children you must believe you’re doing some fine and righteous thing. No doubt there’s comfort, maybe pleasure, too, in the bonds of solidarity—facing danger together, protecting your young. But isn’t the point of the story of Abraham and Isaac that God does not require us to sacrifice our children for our beliefs? Much less, I’d guess, to satisfy our own sense of righteousness and heroism.

I wander towards the crumbling dwellings and am naively surprised to find that, from here on up another winding hill, Israeli Defence Force soldiers are stationed at about 30 metre intervals, each small group of two or three within sight of the next. I realise that this is now a ‘mixed’ area: Palestinian families are still living in shabby housing here, much of it empty, some derelict, behind the biscuit coloured ruins. It is eerily quiet, just a few elderly men shuffling past, no traffic except for the occasional army jeep. (Palestinians, I learn later, are prohibited from driving cars here).

I walk a couple of hundred metres more, past another half dozen armed foot patrols, and find a barely stocked grocery store where I stop for a bottle of insipid “lemon flavoured 0% beer.” A gaggle of small Palestinian boys, who were kicking a ball around outside, run over to inspect me, ask my name and age, try on my sunglasses, which get dropped and broken in the process. From a yard beside the shop, partially screened by a bamboo fence, we are closely observed by two teenage girls, one in a wheelchair. I’m glad that they don’t come out. Wouldn’t be considered proper; and they might point at the crippled girl’s spine and say “Israelis” and I wouldn’t know what to believe. The boys tire of me and go back to their ball. A sliced kick sends it towards a couple of soldiers standing opposite, and one of them kicks it back. Four Orthodox youths, perhaps from the earlier football game I saw, pass jauntily by, out for a stroll, it would seem. Asserting their claim on this place.

I continue, past a bunch of wrecked cars, a metalwork shop behind the closed basement doors of an empty tenement, paths meandering off over waste ground, a man making his way through dry weeds, litter and rubble with a bag of daily flatbread. Not many people left; most, I suppose, intimidated away by now. Wondering if there is another way out of here, I ask a couple of the army patrols but they just look blank, uncomprehending. Then one group of three confers and pushes to the fore a young man who asks “What do you want?” in English I hear as slightly Australian accented. The nearest route to the Palestinian party of the city, I tell him. He seems confused. “You mean the Arab area?” he asks. “Yes!” (“Palestinian,” I am beginning to realise, is not a term much used in Israeli defence parlance.) “I don’t know” he says. A preposterous response, how could you possibly be on a security detail and not know the way? But I guess there are rules against telling the truth. Then he turns and points west, where the sun is sinking into a spanking new town on a hill about a mile away, behind a high, steel fence. “That’s Israel” he says, none too helpfully, but perhaps trying to give me a clue. I retrace my steps.

These heavily armed youngsters will be just out of high school, doing military service before college. Probably longing to be back in Tel Aviv, lounging on the beach or drinking beer in the many, trendy bars (which, I later learn, do not serve customers until they’ve completed their patriotic duty). These boys may not be religious themselves, may well regard the Orthodox families they’ve been sent to protect as screwball fanatics. But it’s the fanatics who are on the front line here, and the secular, democratic, gender-equal, militarily proficient state of Israel is right behind them.

My exit from the West Bank involves a more explicit, but thankfully shorter, ritual humiliation than my entry.

I’ve made my way north to the town of Jenin, aiming to cross into Israel proper near the Sea of Galilee, and from there back into Jordan. In Jenin, I lodge at the Cinema Guesthouse, a failing solidarity-tourism project. German filmmakers rented it a few years back, planning cultural revival for a small cinema—Palestine’s first, established in the 1960s, but since shut for decades. The filmmakers made a couple of documentaries but the funding ran out and the building is now slated for conversion to a shopping centre. I don’t have a reservation but am let in by a guy with a key who sells coffee on an adjacent street corner. There is only one other guest in the three upstairs dormitories and large kitchen-dining area, a young American busy over her MacBook, possibly of Palestinian heritage, but I don’t find out because she is not talkative, seems annoyed to have her peace disturbed. So I go out to explore the town.

Up the nearest hill to catch a view of the luxuriant, Israeli valley I’ll cross tomorrow. A chubby boy, another Mohammed, begins to bounce around me in the street, attracting a small crowd of older lads who want me to take pictures of them. A man is looking down from a window in a middle-class apartment block and Mohammed says that’s his dad and I must come up to meet the family, and he won’t take no for an answer, so I trail after him up three flights of stairs to explain and apologise. I am not a child molester, honest. But they insist I come in. Mohammed’s younger brother is playing Grand Theft Auto, or some such, on a vast flat screen. Dad, dark, handsome, serious, is in the Palestinian Authority police force, a weapons instructor. (I didn’t know they were allowed guns.) This detail is conveyed, after she has made and carried in the coffee, by a lively, pleasant daughter of high school age. I commend her English and she laughs and says she learns from watching movies. (Not, evidently, in the Jenin cinema.) Mum’s out shopping. I think Dad worries that his daughter is too forward, and he makes her put a headscarf on when we all go up more stairs to show me the view from the roof. He went to Tel Aviv once, he tells me, for training. He saw the Mediterranean. It was—he pauses for a long time, looking for the English word—“beautiful.” He would like his children to see it one day.

It’s only ten minutes in a shared taxi next morning to the territorial boundary. The taxi carries several men and one woman crossing over to work. We file down a passage of steel rails to the bag scanner where a uniformed woman roots out my camera and instructs my fellow travellers to tell me not to take pictures here. They translate her Hebrew into mime. Then a gate locks behind us; we pass our documents in at a door, and step back into what is in effect a steel cage, hardly bigger than an elevator compartment, with another steel door locking in front of us and cameras watching from above. This is not security. Across the world, tens of millions of airline passengers are screened every day without being locked in cages. This is the flaunting of might, a deliberate, daily reminder of subjection. And a casual insult to the Muslim woman, crammed against six men she doesn’t know, on her way to wash someone’s floor.

On the other side I take a taxi with a couple of my new companions to the town of Afula, where they insist on walking me to the bus station and finding the right stand for my onward journey. But I decide to look around, find the new train line that passes through from Tel Aviv to the border town of Bet She’an.

Afula is quiet, prosperous, subdued in the afternoon heat like Spain at siesta time, but neater and more orderly. Mid-rise apartment blocks along grid streets shaded by young trees. No litter. Green bins on every corner. Cars stop at pedestrian crossings. Flowerbeds between palm trees down the central reservation of main streets. A row of cafes with pavement tables. Plenty of tanned flesh, short skirts and sleeves, no Orthodox garb here. I have a slice of pizza and a beer.

No one can direct me to the train. No one, it seems, speaks any English—Russian is more widespread, to judge from public noticeboards—and no one here seems inclined to mime. I walk for half an hour in what must be the right direction, making a few fruitless enquiries along the way, thinking about how googlemaps cuts off another avenue for the contact between strangers that civilizes us, imagining what towns will look like when there are no more signposts. I reach a roundabout where a taxi pulls over, makes a phone call to an English speaker who says the driver will take me to the station for 40 shekels. I get in, the car crosses the roundabout, travels 200 metres down the road and drops me at the station. That’s at least three times the meter rate of black cabs in London.

The ten-minute train ride is swish as Germany and the fields through the window as productive. At the other end I ask a girl at the station’s information desk how I can get to the border and she tells me there’s a taxi rank outside. There are no taxis, but a bus is parked, idling at one of several stops, so I go to ask the driver if any routes pass near the border, but he won’t open the door, just looks through me. I stand for ten minutes in the insufferable heat by the empty rank and then go back to complain to the information girl. You have to phone, she says. But my phone doesn’t work here.

I set off marching petulantly along the verge of an empty highway. It would serve them all right if I collapse and die of heat exhaustion, the thwarted child in me cries out. Only several kilometres later, when a passing taxi stops—a kinder driver, who drives a softer bargain—am I able to reflect more coolly on this abrupt transition from one of the most hospitable places I’ve ever been to one of the least welcoming. There’s no reason anyone here should welcome me. Centuries of exclusion and persecution elsewhere have left no historical debt of civility to repay. And I’ve experienced no hostility, merely indifference. But perhaps indifference to outsiders is the other side of Israel’s legendary self-reliance. Culminating in absolute determination to go on building a homeland no matter what anyone else thinks, says or does.

Back in Amman, I read of Mahmood Abbas’ renewed calls at the United Nations for a “two-state solution.” From afar, this always seemed the decent thing, but from what I’ve seen it is now too late. Nibbled away by decades of annexation and settlement, the remaining West Bank is a series of poorly connected leftovers, even further cut off from Gaza (which Israel, the Palestinian Authority and much of the world at large have spent the last ten years punishing for having the temerity to elect an ‘extremist’—Hamas—leadership). This patchwork territory is no foundation for a viable state even if Israel were willing to see one emerge.

I also come across an excerpt from a memoir by Shimon Peres where he boasts about persuading France to make Israel a nuclear power. Only nuclear weapons, he believed, would deter Arab efforts to wipe Israel off the map. Perhaps he was right. But the existential threat to Israel has retreated. The arcane kingdoms and dictatorships of the Arab world are preoccupied with other power plays, fratricidal enmities and the perennial struggle to keep their own people in subjection. The plight of Palestinians may continue to be deployed as a tool in those struggles and power plays, and occasionally bemoaned in global fora, but there is no sign of ‘international pressure’—regional or global—halting, let alone reversing, the ongoing process of dispossession and displacement. I don’t believe the settlements will ever be returned.

A one-state solution is more theoretically plausible but seems equally remote. More than a million Arabs in Israel have accepted Israeli citizenship, although in practice theirs is second class. If the five million or so people in the West Bank and Gaza joined a ‘binational’ state, Palestinians would comprise nearly half—and, given demographic trends, eventually a majority—of the population in a functioning democracy (whose institutions, it should be noted, include civic groups promoting equal rights, monitoring and denouncing Israeli government abuses). But on neither side is there much sign of movement in this direction. I am guessing—for I cannot pretend to know—that many Palestinians would see it as defeat; that many Israeli Jews would never countenance becoming a minority in their ‘homeland.’ And that is without considering the rights to return of the respective diasporas.

It was an unsettling trip. I saw enough to make news reports intelligible, and to avoid easy opinions. ‘Complex and intractable conflict.’ I come away knowing more about the weight of words like this. I don’t expect to see a fair and durable peace in the Middle East during my remaining lifetime. I hope my grandchildren will.

- 5929 reads